An Interview with William C. Crawford, Class of '66

By Eli Bostian

Several weeks ago, I had the opportunity and pleasure of interviewing William C. Crawford, the photographer responsible for multiple accepted photography submissions to The Phoenix, the Spring 2015 issue cover photo “High Flying Laundry”, and the exceptional nonfiction submission “My Last Day with Ollie Noonan.” As a student, Crawford reported for the papers of both his high school and Pfeiffer College and was a military photographer during the Vietnam War. In reaction to his wartime experiences, Crawford explains he “shut out Vietnam” and as a result spent many years of his life without pursuit of the old hobbies he now enjoys once again. Crawford’s reporting talent became quite evident within minutes of our interview as he calmly adjusted to the clumsy and inexperienced methodology I employed in providing him questions. Thanks to some advice he provided to me in the middle of our interview, I was able to complete the interaction with minimal embarrassment and now mark the experience as a turning point in my own approach to future interviewing endeavors.

William Crawford graduated from Pfeiffer College (now Pfeiffer University) as a history major and secondary education minor in 1966 and now lives in Winston-Salem, NC. He pursues photography of the “trite, trivial, and mundane,” classifies himself as a “semi-professional or serious amateur,” and leads a truly remarkable interview.

This photo of the young William C. Crawford was taken at Ft. Hood, Texas, in 1970 by Sp.4 Jim Provencher. Provencher is the accomplice mentioned in this interview who took part in the recent Texas photo shoot.

Eli Bostian: How did you first become interested in photography?

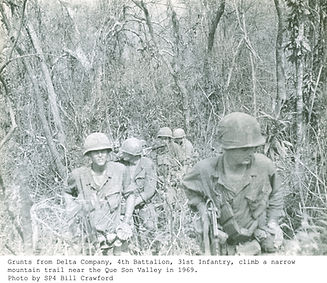

William Crawford: Did you read “My Last Day with Ollie Noonan” (Please see the 2015 edition of The Phoenix)? Well, that pretty much describes how I got into photography. I had written for the Pfeiffer newspaper when I was there, and I had written a little bit in high school for the high school newspaper. However, when I was in Vietnam in the infantry, I ran into a guy who was the combat photojournalist for my battalion and was going home. When he found out I had some writing experience, he asked me if I would be interested in applying for his job, and he put in a good word for me. They wanted somebody who was conversant in 35 mm photography, and this was in 1969 in Vietnam, so I sort of fudged… ah, lied, outright, and said I knew how to do 35 mm photography, but I didn’t. I got the job, learned on the job how to become a photographer, and had the fortune to be exposed to a lot of the great wire-service photographers of the Vietnam War by coincidence. They just came through my area when we were in some big battles, including one of the largest battles in the entire war in the summer of 1969 with some of the biggest names in combat photography in the Vietnam War, and they helped me along with my photography. So I went from knowing nothing to learning quite a bit and being a passable photographer by the time my tour was over. It was a life altering experience; the people that taught me are now legends.

EB: I’m humbled to think about it; I can’t believe what it must be like to think back and remember that.

WC: For many years I shut out Vietnam because combat was… an unpleasant experience, to put it mildly. And for forty-some years, I had tried to write the Ollie Noonan remembrance, but then a couple of years ago, now that I’m mostly retired except for a small photography business (which doesn’t take a huge amount of time), I was finally able to sit down and write that piece and re-contact some of my old Vietnam acquaintances, a lot of people I’d shut out for decades. I even met up with George Hawkins in San Francisco, the photographer whom I replaced and who probably saved my life; my original infantry company suffered massive casualties later in the war after I had the photography job, and I would have been there had I not gotten the job. I would have been almost certainly killed or badly wounded.

So I sort of made peace with my Vietnam demons, and now I actually realize it may have been one of the most… it was one of the most important and exciting times of my life despite the horrors of the war, especially with the interactions with those soldiers (I stayed attached with the same unit after I became a photojournalist), with my fellow soldiers, and those wonderful, mostly Associated Press combat photographers and journalists (like in the First Gulf War, Peter Arnett, who has a couple of Pulitzers and was still reporting as recently as the 90’s, I worked with him, and Horst Faas who’s got some Pulitzers, the German photographer who died a couple of years ago and was the head of the AP Saigon Bureau Photographers Section… there’s just a lot of people that I worked with that are now sort of immortalized in the annals of combat photography). Now, I’m not indicating that I am in any way in their class, but they did give me tips, were very helpful and supportive, and I still remember a lot of what they taught me even these many years later. Even with all the changes now to digital photography, a lot of what they taught me still is applicable, and I practice a lot of it even when many modern photographers have moved on to other techniques.

EB: It says a lot to the value of the techniques themselves that you can apply them even with the differences in media from film cameras to digital. Do you still take any photography with film cameras?

WC: No, during my period of trying to forget Vietnam (which was a big mistake in hindsight), part of those mistakes that I made was selling every single camera and lens I had, so more recently when I got back into it I had to start from scratch. I deeply regret that decision, but it was psycho-emotional more than common sense.

This is a complicated situation; what I have tried to do was tell you about the Ollie Noonan story which, of course, is a remembrance of a friend’s death, but it’s really a lot bigger than that in my life. The telling of that story, finally, after all those years, has opened back up my participation in photography after a long hiatus, and it’s certainly been a personal catharsis that enabled me to finally embrace what happened in Vietnam rather than trying to hide from it.

William C. Crawford and his wife Beverly at Yosemite.

EB: It’s certainly been beneficial to us all.

WC: Well, I think a lot of people have enjoyed this story; it’s just straightforward journalism. It’s not written in a very deep literary style, but it’s just a journalist’s account of what happened.

EB: Sometimes that can say far more in any literary sense than even an epic.

WC: I tend to write in the straightforward style, somewhat epigrammatically, and I’m not probably a very gifted literary writer with any particular literary style. I just sort of tell the story straight out, and I have some talent for capturing it in that way and not so much for the metaphorical or other devices.

I could tell you a little bit about my current photography if that would be helpful. I have a credo that I’ve already alluded to a little bit, a retrospective credo… I utilize the wonderful advantages of digital equipment, but I forsake almost all computer manipulation in post-processing after the image is shot. I still shoot the old way, attempting to do the best composition and camera control settings up front, just like it was still-film. And so what I am sending out, putting out, producing, whatever, is pretty much straight out of the camera images. I employ no device or manipulation that wasn’t available back when we used to process film and print in the dark room. It uses no technique that wasn’t available in the dark room in 1985 (just a cutoff year I’ve selected, it’s irrelevant really), but all of the modern computer manipulation, Photoshop, Light Room, that type of thing, I use none of that. So I’m basically using the new sensors, the new digital sensors, and the cameras that have them, but most of my technique would have been available in 1985 and it’s built on basic shooting techniques that a beginning photographer would have been taught back in the days of film. And then, with almost no computer manipulation, my images are what they are. This is a very radical approach, and I’m not attacking any photographer that uses Photoshop, any computer manipulation, but a lot of the good photography that I see now, although the images are spectacular, is more a product of computer technology than photography. I prefer to continue to emphasis the photography. In terms of subject matter, I’m a street photographer, which is a polite way of saying that I shoot a little bit of almost everything, but I try to emphasize the trite, trivial, and mundane; that is to say I take very common, everyday images and try to make them interesting enough that somebody would derive something from seeing the image. Now, even in everyday street shooting, you sometimes encounter a dramatic photo that just presents itself, so sometimes I do see some things that might eclipse the trite, trivial, and mundane (say, a spectacular sunset), but it’s only because I sort of encountered it by chance.

EB: How often would you say that those occurrences happen?

WC: Spectacular ones? Well, I just went to Texas on a photoshoot with an old army buddy about a month ago; we were down there eight days, he was here from Australia, and I took this opportunity to shoot again with him after 40 some years of not shooting with him. In a place like west Texas (we were around El Paso at the border), because of the border, because of the situation of the border, because of the west Texas desert topography, I probably shot 1000 or 1200 frames down there, and I actually got 10 or 15 that are pretty spectacular to me, and some that would be spectacular to the casual viewer. Some are spectacular maybe to me only because of my rather unique criteria that I apply to photography; the simplicity straight out of the camera, that matters much to me, but maybe not so much to other people, so, when I shoot that many shots on a trip, in a sort of cool place, a unique place, sometimes in a thousand shots I might get ten or fifteen that are pretty extraordinary. If I’m shooting here in North Carolina, up here in Winston-Salem, I might go several months and only shoot one or two that are really extraordinary out of several hundred. But, eventually, the big thing about photography, the kind that I do, because I’m shooting the trite, trivial, and mundane and grabbing a few sunbursts as I happen to encounter them, the big thing for me is to keep shooting. I’m 71 years old, I force myself out the door and even in some of this rough weather we’ve been having, and I shoot four or five days a week. Sometimes it might be I’ll get in my car and go somewhere and stop, and shoot there for thirty minutes; if I get cold I’ll stop, and sometimes most of those images I discard. But I could send you three images that I shot on a day recently here in Winston-Salem that are pretty cool shots.

And so that’s what happens. Because I was out there, I got them. And they’re off-the-wall, sort of abstract items that don’t matter to anybody, but all three are strong photos… I walked out of my door, drove in my car, shot for less than an hour, and I encountered these in a neighborhood here in Winston-Salem. I do that all the time. I shoot more than 10,000 images a year (which wouldn’t be so high for a professional photographer), but that’s quite a few for an amateur. I am “slightly-professional”, I do have a business card, and I do a few small jobs, but I would consider myself more of a semi-professional or a serious amateur; I’m not really a professional.

EB: What program did you study under when you were a student at Pfeiffer?

WC: I was a history major and a secondary education minor because I planned to teach at the high school level at the time. I came to Pfeiffer on a chemistry scholarship after I found that I had done pretty well in the natural sciences in high school, and I had an uncle who was a chemist in Virginia, you know, with paper mills and pollution prevention (although this was so long ago it was rudimentary anyway). When I got to Pfeiffer, back then the science department was extremely rigorous, all the biology, physics, chemistry, and of course the related department of mathematics, and when I found out just how rigorous that was, I also found out something about myself that I never realized—I hated all of those hours in the lab, deep into the afternoon, just hours and hours and hours, and I realized that I couldn’t ever do this. That’s when I switched to history. I picked that only because I just enjoyed it, and, at that time, I didn’t really have a life plan, and it was a good choice. At that time, the history department was good at Pfeiffer, and I had a pretty positive experience back then and I definitely got rid of labs.

EB: Would you consider the circumstances surrounding your photograph “High Flying Laundry,” which we are using for our cover, to be spectacular?

WC: Well, as an isolated photograph, it is probably not spectacular, but the backstory of all of it to someone like me makes it somewhat spectacular. Briefly, it’s taken in San Francisco, one of the most spectacular cities on earth. It’s taken in North Beach, one of the funkiest and most popular subdivisions of San Francisco. I took it after just walking out of the famous City Lights bookstore, one of the most famous bookstores in America and very prominent in American Literature (you know Jack Kerouac and all those beat poets, Allan Ginsberg and all of those people not only hung out there but some of them helped to found the store, and so when you visit there, it’s like you’re dipping into a literary history and a whole movement, the beat generation of the fifties was there). So I walked around the corner and down an alleyway—my wife was still in there, you know, buying something or whatever, in there, in there interminably—and so I shoot out into the alley, turn a corner, and shoot the “High Flying Laundry” and I got a couple of other shots of windows around there, and the alley itself, and graffiti and all kinds of stuff. All that backstory, considering everything I’ve said, makes it spectacular to me, but that’s a part of the personal experience that’s so… that shot is quintessential San Francisco, with its heavy Chinese-American population and their penchant for hanging their laundry in high places just outside of their dwellings, which are often also in high places like apartments of course. So, all of that to me makes spectacular photographs, but maybe in isolation, the first time viewer of the image might or might not, depending on their background and knowledge, be able to dip into some of that; and they might be able to guess where it was shot, or they might not.

EB: Do you have any suggestions for anyone who feels creatively stifled with any of their attempts to capture things spectacularly, with any of their attempts to capture the mundane such that others will be able to see what they see and understand?

WC: Well, I’m a good example, I think, of a person that has little creative or artistic ability. I can’t sing, I can’t draw, you know, I don’t pot or do sculptures—I’m just terrible in all of those areas—but I happen to have a little talent that you can only find if you get out there and try something. My talent is that I can see possibilities for photographs where other people see nothing or see little; I can tell a story in the straightforward, epigrammatically, journalistic way; and the other artistic talent that I have that’s kind of unrelated but people tell me that I am a great judge of is pottery. People ask me to pick out pottery as gifts sometimes, my wife and other people… and I’m just working around to say that even when you are terribly challenged in artistic areas and feel like you can’t do anything, I’ve found out over decades that I have these three talents, and the important thing is to get out there. It’s like what I said about the photography: you have to get out there and try something to find out if in fact you have a talent that’s hidden, or not totally cultivated yet, and feeling stifled is not uncommon. I have many friends who are excellent writers, with multiple books published and that type of thing, even recognized artists if we want to call them that, all of whom face problems with being stifled and blocked, but the thing to do in my case is to keep shooting, or keep writing, or whatever the medium is.

The Phoenix staff would like to thank Mr. Crawford for the use of his photograph, “High Flying Laundry,” the additional photographs he provided for publication with this interview, his nonfiction submission “My Last Day with Ollie Noonan,” and as his interest and efforts in the completion of this interview. I would personally like to extend my thanks for the opportunity of getting to know Mr. Crawford and look forward to any submissions he may provide us in the future.

Some final words from Mr. Crawford:

Something important in all photography to me is something I call ‘the funk factor.’ And you can define that as you will, and whatever you define it as probably captures some of what I would define it as, but funk is funk, and you just sort of have to know it.

This is an example of the trite, trivial, and mundane, and what you can get just by getting up off your butt and shooting.

William C. Crawford at

The Phoenix's Spring Launch Party.